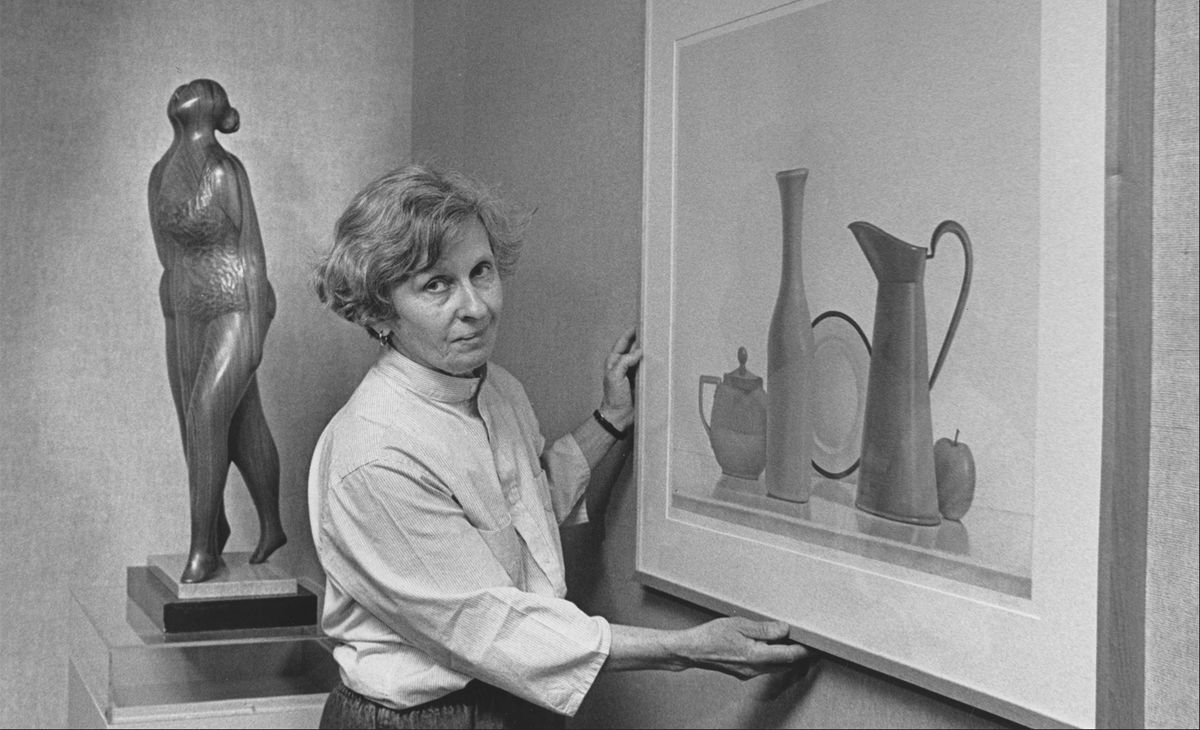

Evelyn Keyser hangs her sister Elsie Manville's painting for a show in the Diamond Club. Evelyn's wood sculpture is shown in the background. Photo by Robert Dias, 1988.

In 1939, Elsie Manville, a talented young painter, was awarded a scholarship from the Board of Education of Philadelphia to attend the then-Tyler School of Art at its original campus in Elkins Park. Elsie’s twin sister, Evelyn Keyser, was an equally bright student and talented artist, but their parents could not afford a second tuition. Fortunately, Tyler Dean Boris Blai learned of their story and took it upon himself to pull together the funds to cover Evelyn’s admittance as well. Following their time at Tyler, both Evelyn and Elsie went on to have uniquely impactful careers in their respective fields of sculpture and painting. The opportunities closest to home included serving as award-winning Tyler Fellows and exhibiting their work at Tyler in multiple exhibitions.

Without the generosity and discretion of Blai, Evelyn would not have been able to attend an art school, and with that in mind, Evelyn’s daughter, illustrator Deborah Dion and her husband Alan Dion (Temple Law ‘72), have endowed the Evelyn Keyser & Elsie Manville Memorial Scholarship Fund, which will provide an annual scholarship to a student with financial need who is enrolled in an art program at Tyler.

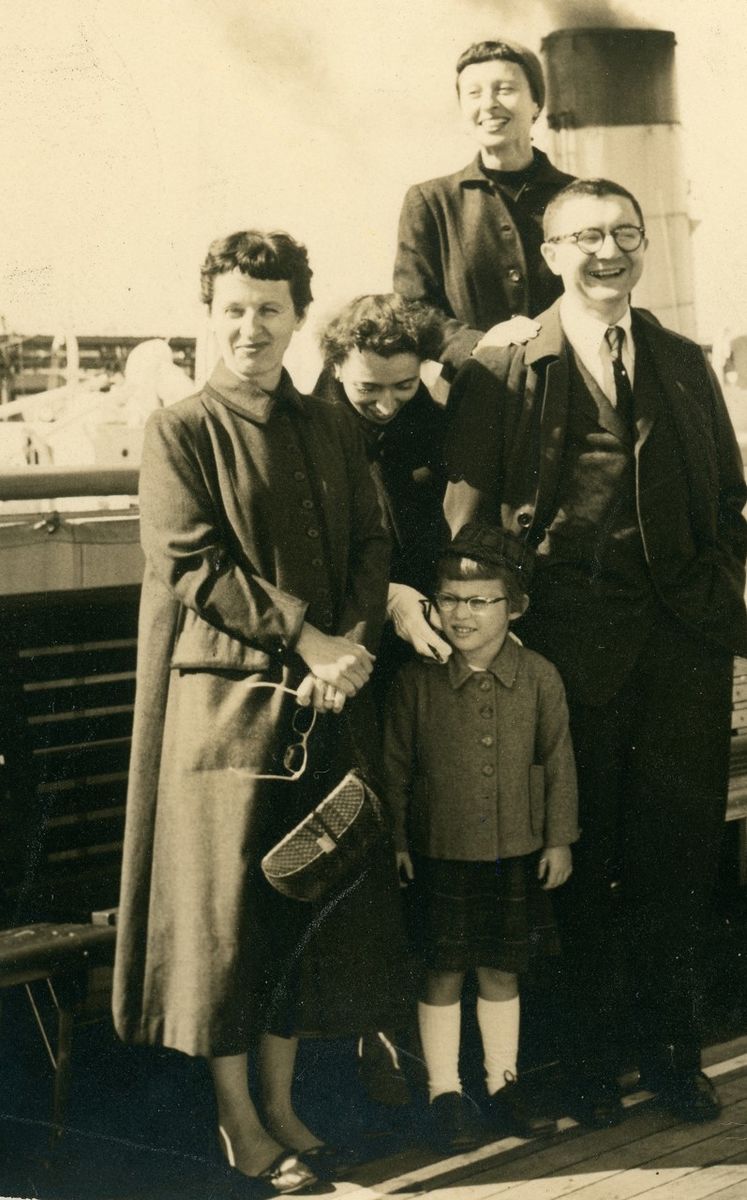

Evelyn and Elsie attended Tyler through World War II, a time period that informed much of their work. Their parents emigrated from a Polish region of Eastern Europe to the United States in 1913 and 1914. Their mother’s family perished in a Nazi concentration camp, and the psychology of survivor’s guilt, loss, and family followed Evelyn and Elsie throughout their lives and careers, Dion said.

Evelyn (far left) and Elsie (second to right), boarding a ship to Europe in 1953. Photo courtesy of Deborah Dion.

After their graduation from Tyler, both Evelyn and Elsie went on to work with N.W. Ayer and Son, a prominent advertising agency in Philadelphia where they created drawings and ad mockups. From there, both women found success in the fine arts. Elsie taught painting at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City, held many exhibitions of her work, earned gallery representation with Kraushaar Galleries, and spent a year working in Italy. She also earned two National Endowment for the Arts fellowships and sold many of her canvases for over $10,000.

Evelyn shifted from illustration back to sculpture and formed a working relationship with architect Norman Rice of the Mid-Century Modern School, who later designed her and her husband’s home in Elkins Park, next to Tyler. Evelyn worked on nine public commissions with the city of Philadelphia, one of which was “See the Moon” a sculpture that sits outside of the Philadelphia Free Library on Broad and Morris Streets. Dion describes her mother’s work as always “having an edge. It was modern before its time. It also had a very Zen quality about it.” Evelyn’s most successful years commercially were with the Gallery Joe in Old City.

Both Evelyn and Elsie conveyed the importance of art to their families in their everyday lives — “You get up, you put the dishes in the sink, you don’t worry about making the bed. You go to work and put all of your energy into your art, and then you come home and do what you need to do,” Dion said, remembering the seriousness with which her mother and aunt took their practices. The sisters were close with each other throughout their lives, though the shared trauma of their family history sometimes meant they faced “what people thought were stereotypical artist’s mood swings,” Dion said. However, if one sister wasn’t doing well, the other was always there to help. The last few years of their lives were distant, since Elsie lived in New York and Evelyn lived in Pennsylvania, but they did occasionally speak. Evelyn passed away in February 2011, and Elsie about a year later, in 2012.

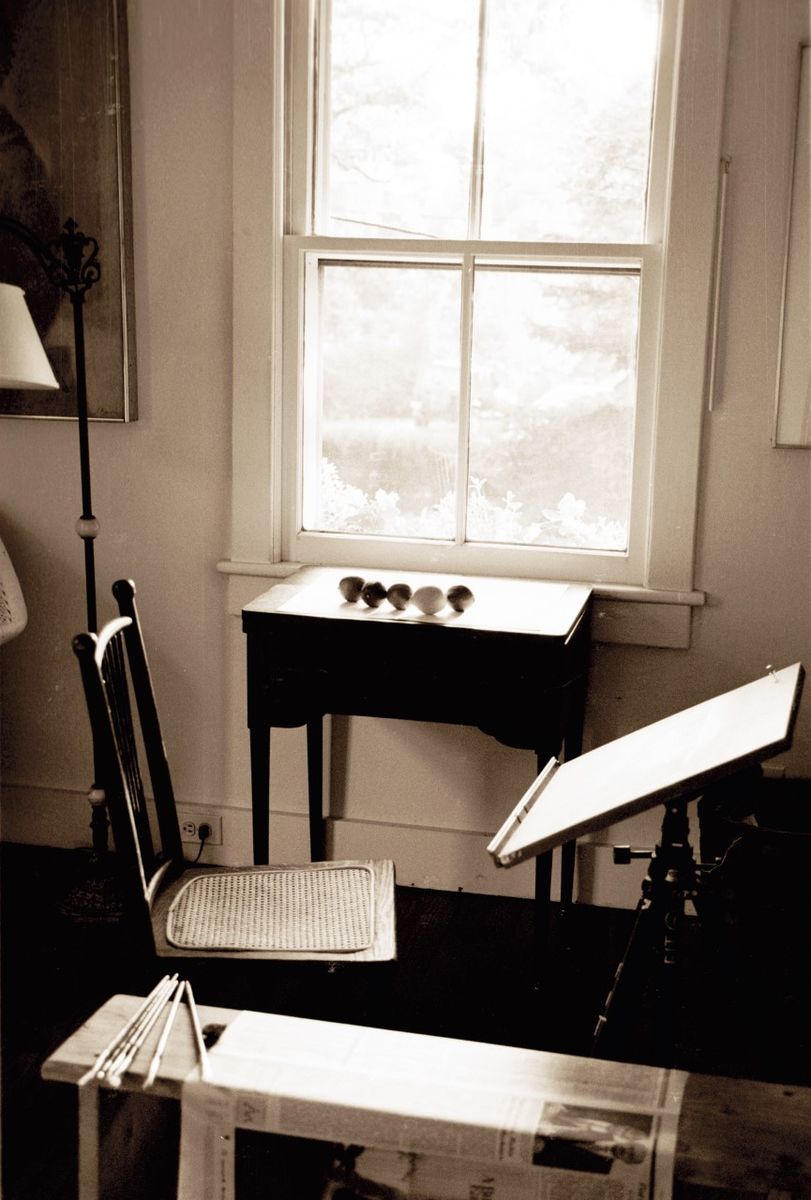

Evelyn's studio in Elkins Park, photo courtesy of Deborah Dion

Dion felt the impact of growing up in an artist family and learned her craft through “osmosis,” she said. Her father was an illustrator and a painter, so she was around art galleries and exhibits frequently, and Evelyn familiarized her with all the tools of a sculptor and woodcarver. Evelyn taught Dion to sew and encouraged her to take up music, though neither parent was insistent that their children should be artists and encouraged them to be whatever they wanted. Though Dion did go on to become an illustrator, her brother Daniel is an accomplished meteorologist and Elsie’s daughter Hope worked as a successful copywriter in New York. Attending Tyler gave Evelyn and Elsie a “sense of sophistication,” and that experience shaped the way they approached several aspects of their lives and the goals they set for themselves and their families.

Dion recalled how “Evelyn and Elsie’s years at Tyler were really special to them. It was a place that felt like going home to them. I think they would be very happy and would ask me if they could give money to support the scholarship.”